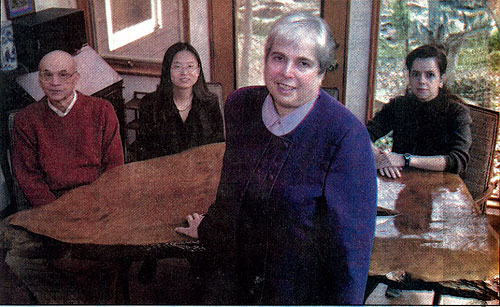

Photo by Isaac Manashe Advocate for the child, adviser to the parent: Dr. Pat Webbink, a psychologist with extensive experience in treating teenage depression, stands with her associates, from left, Dr. Morton Werber, licensed social worker Mindy Thiel, and Dr. Patty Porro-Salinas at Webbink's office in Bethesda, Md.On Shaky GroundDespite a parent's best efforts, helping a teen in the grip of depression can prove an elusive, daunting process best left to a therapist.By Lynn L. Remly "Depressing" is a word used by young people every day in many contexts — a disappointing score on a test or a car that fails to start can lead to the feeling of being "down," "depressed" or "bummed." though the term depression describes a range of normal human emotions, it also refers to a serious mental illness that may require medical attention. But even in today's more accepting environment, the symptoms are often hidden or ignored, leading to delayed diagnosis and the potential for deeper problems. "Depression does not necessarily lead to suicide, but it is a major risk factor for suicide," said psychologist Dr. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology in Washington. "Depression is involved in between fifty to sixty percent of all suicides, and the data for teens is about the same." Each year, 500,000 people aged 15 to 25 years old attempt suicide — 5,000 succeed. The observable warning signs of depression are the same for adults as for teens, Berman said, though young people often act out their symptoms, such as sadness, in a more agitated or aggressive way. "Their hormones are raging," said Dr. Patricia Webbink, a psychologist and noted authority on teen depression whose offices (along with her colleagues) are in Maryland, Virginia and Washington. "There's so much going on in a teen's life; one minute everything is fine, and the next minute their world is falling apart." Sadness, talk of suicide, sleeping problems, loss of appetite, weight change, fatigue or a decline in energy level, loss of concentration or a lack of interest in pursuits that were formerly interesting--all are symptoms of depression, and parents need to take note. "Often, parents have blind spots that make it difficult for them to be aware of a child's depression," Berman said. "Often, too, kids will say more to their peers than to their parents. In psychological autopsies conducted after a person has completed suicide, we often find that a peer knew of his friend's thoughts of suicide." Because of the bonding among young people, teens are reluctant to report any concerns to a friend's parents, however. "It's part of the value of their friendship. It's not wise, but it's understandable," Berman said. Webbink said it can be a tremendous help for a young person to have a trusted confidant, "someone who's an adult, but also an ally." That's because the teenage years are the time when young people often begin pulling away from their parents. "This is a healthy thing, of course, but it's tough on both sides," Webbink said. Webbink described a therapist's role is as an ally, a person a teen can trust who still has an adult sense of what's appropriate or dangerous. Above all, Webbink said, a therapist needs to establish a bond so the young person doesn't feel the therapist is just the parents' agent. Teens today are faced with pressures and problems never dreamed of by pervious generations, Webbink said. "They have to make mature decisions when they're not mature. They might listen to me, but if their parents told them to do something, they might tune it out." According to Maria Eugenia Delvillar, outreach coordinator for the Teen Parenting Program in the Arlington Public Schools, depression relating to pregnancy and post-partum depression are significant concerns among teens, especially Hispanics and African-Americans. "The girls are worried about how to cope; they're worried about the reaction of their parents and partner—they're overwhelmed," Delvillar said. Arlington's program, which helps about 200 girls each year, works both with girls who are pregnant and those who are already mothers. Overall, the effort is geared to keep the girls in school and help them deal with the stresses of a (usually) unplanned pregnancy. In both causes, follow-up is critical—young mothers must realize they still have a future. "The depression doesn't stop with the baby," Delvillar said. "The problems get worse when the child is two to three years old, and the mother herself is still young." Helping a depressed young person gain new insights is the goal, Webbink said. "Suicidal teens tend to have tunnel vision and to think that it's the end of the world if someone won't date them or if they get a low grade on one test. It's the therapist's job to ease their fear and calm them down by widening their perspective, taking off the blinders, and giving them an alternative way of viewing issues important to them." But it can be difficult for parents to distinguish their children's everyday problems from those that could lead to suicide. "It's not their business to distinguish despair and suicidal risk," Berman said. "That's the job of a professional. You wouldn't let a child continue with unremitting fever; you'd take him to a doctor. It should be the same with depression. Parents should get help from a mental health professional—a psychologist or psychiatrist—who can evaluate the teen's condition." It can be difficult to get a teen to go to a counselor, Webbink said. "They often consider it shameful." She recommended approaching the subject by asking the young person to see a counselor just once, as a favor to the parent. If that doesn't work then a compromise might, such as a agreement to let the teen have an extra privilege for going to a counselor. "It very often happens that when they come the first time, they like having someone to talk to and are willing to continue," Webbink said. There are several ways to get referrals on qualified mental health professionals, including asking the child's primary care physician or family doctor, or calling organizations such as the local Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis Referral Service. It's also wise for parents to check with their insurance company for any coverage limitations on mental health treatment. Webbink's office offers a sliding payment scale to better match each family's means. "Our culture still underestimates the significance of emotional issues, and often, insurance coverage is minimal," she said. It's also important to find a therapist who both the parents and patient can work with, which may mean consulting more than one until the right match is found, Webbink said. "The right balance between a therapist's style and a client's needs is vital to developing a trusting, safe, non-judgmental relationship." |